The Need For Artificial Intelligence: Increasing Global And Human Complexity

Beyond “The Good Old Days”

Some people like to reminisce. They wish they could return to a less complex world without the unending stream of news, email and social media. They preferred life when there were fewer people, less traffic, and cheaper groceries. They miss when there was no constant threat of terrorism. They want to return to “the good old days.”

Despite this desire to return to supposedly simpler times, we cannot turn back. Our world is vastly different now compared to even a few decades ago. Because of phenomenal advances in medicine, housing, transportation and many other areas, Earth now supports a population of over seven billion people. It is estimated that by 2030, global population will reach 8.6 billion. [1] Sustaining such numbers demands strong interconnectedness and reliable communications. Unfortunately, more people also create increasing pressures on resources: water, energy, food, rare earth metals – all are more difficult to acquire.

Moreover, we are living in a veritable data explosion. In 2012, the amount of information generated over the internet doubled roughly every 1.25 years; [2] it is assuredly even faster now. Every day now we create 2.5 quintillion bytes of new data. [3] This data tsunami tasks our local and federal governments in gathering data, comprehending it, and crafting sound policies.

Additionally, societal changes will further intensify with development and deployment of new technologies. Fundamentally, we have taken evolution into our own hands. [4] We now live far longer than the average lifespan of roughly 40 years only a century ago. The on-going merger of man and machine (biological and digital) opens new vistas for us in knowledge and entertainment, but it also further amplifies the needs for information recording and processing.

The only way we can survive and thrive in this constantly changing and increasingly complex world is to get assistance from our machine creations. Artificial intelligence (AI) must be a core aspect of that help, as it offers unprecedented capabilities to monitor, control and assess a wide range of situations. AI will not (at least in the near term) remove the human from the loop; instead, it will augment our capacities for better data collection, analysis and decision making.

Increasingly Complex World

“Indeed, developments over the ensuing quarter century have revealed a far more complex reality, one of much less international consensus on what constitutes legitimacy in principles, policies, and process and not much in the way of a balance of power in practice. This more uneven, complex world has been quite disorderly, a conclusion that emerges clearly through an examination of the major historical events of this period, the gap between global challenges and responses, and regional developments.”

--RICHARD HAASS, A World In Disarray: American Foreign Policy and the Crisis of the Old Order

From early 2015 to late 2017, I had the honor and privilege to serve as the first National Intelligence Officer for Technology (NIO-TECH) within the National Intelligence Council (NIC) of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI). As NIO-TECH, I had the opportunity to contribute to the Global Trends: Paradox of Progress [5] publication that was submitted to the incoming Administration on January 2017. In this well-researched report, the NIC laid out how economic, political, social, technological and cultural forces collide and might affect our future out to 2037.

The core theme to this recent Global Trends is how there exists a paradox in our progress as we have developed our world:

"We are living a paradox: The achievements of the industrial and information ages are shaping a world to come that is both more dangerous and richer with opportunity than ever before. Whether promise or peril prevails will turn on the choices of humankind. The progress of the past decades is historic—connecting people, empowering individuals, groups, and states, and lifting a billion people out of poverty in the process. But this same progress also spawned shocks like the Arab Spring, the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, and the global rise of populist, anti-establishment politics. These shocks reveal how fragile the achievements have been, underscoring deep shifts in the global landscape that portend a dark and difficult near future." [6]

There are no easy solutions for the issues created by such complexity, but there is a growing realization that better data analysis can help. For example, it is estimated that 99% of the data in the Department of Defense is not analyzed but lies ‘dark,’ awaiting the right analyst or algorithm. [7] An initial push within the Pentagon to tackle this issue is to leverage AI to analyze imagery, thus turning “…the countless hours of aerial video surveillance collected by the U.S. military into actionable intelligence.” [8] For all the reasons listed above, AI analysis is no longer a luxury, but an imperative.

Other countries recognize the commercial and military leverages that AI can provide. China has a major push for AI, with some fearing it will overtake the United States in AI leadership in coming years. [9] [10] In a speech to school children, Russia’s Vladimir Putin recently stated, “Artificial intelligence is the future, not only for Russia, but for all humankind. It comes with colossal opportunities, but also threats that are difficult to predict. Whoever becomes the leader in this sphere will become the ruler of the world.” [11] Canada, Switzerland, Germany and others have major AI initiatives planned or already funded.

AI is seeping into politics, also. New Zealand just deployed the world’s first “AI politician.” [12] Named SAM, the AI bot answers a range of questions on policies for housing, education and immigration. Its creator, Nick Gerritsen, has high hopes for its future. “By late 2020, when New Zealand has its next general election, Gerritsen believes SAM will be advanced enough to run as a candidate. However, it is not legal for AI to contest elections.” There is speculation in technology circles about whether an AI could be a good President of the United States (POTUS). [13]

Overall, we recognize that governance and policies can benefit from AI. Part of that realization may stem from an acknowledgement of our own limitations.

Increasingly Complex Humans

“Evolution is like walking on a rolling barrel. The walker isn't so much interested in where the barrel is going as he is in keeping on top of it.”

--ROBERT FROST, The Letters of Robert Frost to Louis Untermeyer

Nature is a poor project manager. In engineering firms, when there is a big goal there is often brought into the team an expert in planning and operational execution to guide the team toward reaching that goal. This project manager develops Gantt charts, milestones, objectives, and budget, R&D, personnel, and resource plans. Plans are presented to management and, if approved, given appropriate support. All-hands meetings are held, and splinter sub-groups are tasked with specific project actions to contribute to the overall team goal. If the goal is met, great! - the company rejoices in new profits and the team throws a party. If not, people re-group and fix the issues, or move on to other projects (and oftentimes point fingers to who is to blame for the failure).

Nature doesn’t work that way. If one assesses the basic physiology and anatomy of a human [14] today, one would want to fire nature’s project manager. We all carry in our bodies numerous anatomical features that can be considered hangers-on from evolution, the so-called human vestigiality. The appendix, the tail bone, tonsils and other body parts are either not fully required or superfluous to our fundamental operations. So why do we have them? It’s because of the chaotic path that evolution has taken over the millennia. Natural evolution is not project planned, it just happens.

Moreover, we suffer in cold, heat, vacuum and any environment that deviates even a smidgen from the narrow homeostasis [15] that our fragile bodies will allow. We contract cancer and sundries of other chronic diseases. If we are fortunate to live to 90 years old, our life expectancy is only a few years more, whether we are male or female. [16] We require glasses, surgeries, roofs over our heads, central heating in the winter and cooling in the summer, and constant food and drink. We must exercise or our muscles atrophy and our bones degrade. It takes us almost two decades to become independent adults, away from the nurturing environment of our parents.

But isn’t that what being human simply is - shouldn’t we just accept our evolutionary fate? Perhaps, but if so, why have we battled for millennia to overcome our ailments, increase our food supplies, purify our water, improve our hygiene to avoid killer germs, change our environment toward one more benign to our mammalian physiology, and ensure our children live better, longer lives than we do? By doing so, we have increased average lifespans from about 30 years to more than 80 years in some countries.

We might argue that this is purely the survival instinct that all animals possess, but Homo sapiens nowadays go way beyond mere survival. We have the tremendous advantage that we are big-brained and can plan. In a way, we don’t really live in the present, we live in the future as we constantly attempt to anticipate and acquire our next meal / degree / spouse / job / car / house / child / vacation / retirement. We manipulate our surroundings, health and very environment to bend all toward our desire of longer, healthier, and more productive and enjoyable lives.

Our capabilities are so far beyond what even the richest people in the world had available mere centuries ago, it boggles the mind. Years ago, I was touring a beautiful French castle in Loire Valley. After viewing a particularly impressive throne room, my then-manager turned to me and commented, “It was good to be king.” I replied that I’d rather be a commoner now, because we have many more opportunities for education, travel and entertainment; better healthcare; and more access to knowledge than even the wealthiest royalty back in the Middle Ages.

However, we have only just begun our manipulation of matter, environment and body. Our next steps will take us to whole new levels, which will require more than just human minds to comprehend and control our world.

For example, the Internet of Things – comprising devices both digital (e.g., smartphones) and biological (e.g., medical devices and biometric systems) - presents a fundamental challenge in data processing. With estimates of 24 billion ( BI Intelligence ) to 50 billion ( Cisco ) [17] devices connected to the internet by 2020, and over a trillion sensors complementing those devices, mankind is awash in data. How to make anything meaningful of that information for governments and companies is a grand challenge…one that will probably only be solved by advanced AI.

It seems every day in technology news, there is some new market sector embracing AI. Industries of medicine, insurance, finance, autonomous systems, home and personal assistants, and others are embedding AI into their fundamental operations. Why? Because we are limited in our biological processing systems – our three pound brains – in massive data memory and processing. AI can help us to absorb and process this tsunami of information.

Some visionary organizations are embracing this convergence of the biological and digital. In 2015, I had the opportunity to visit the J. Craig Venter Institute in San Diego, California. This institute has as a focus to leverage its earlier mapping of the human genome. [18] When they described how they have as a goal to acquire over one million genomes, I asked how they plan on extracting meaning from them. They answered, “We have a specially-coded AI that does that for us.” Thus, they and others are merging biotech with AI and big data analytics to de-obfuscate what to humans would be mountains of confusing data.

Advances in neurosciences will also accelerate the need for better analysis capabilities. In articles in WIRED, [19] Nature [20] and MIT Technology Review, [21] controls into and from our minds by external means are summarized. Electrodes are surgically implanted in the brain and a map of neuronal activity is attempted to be made. Using algorithmic inputs, those electrodes can stimulate the same neuronal activities in the subject’s mind, with the ultimate goal of developing a commercial neuro-prosthetic to enhance memories. Similarly, those maps can be used to play video games with no physical contact by the patient. Although highly experimental now (and requiring volunteers willing to undergo brain surgery!), several companies, including Neuralink , are researching brain caps that don’t require in-vivo surgeries. Of course, this research raises substantial ethical and other questions. A core unknown is how we would complement our abilities and enable ourselves to process these new data sets to / from our limited minds.

Need for AI

Humanity is at an impasse now. Governments and politicians are struggling to remain on top of a constantly growing set of threat vectors, mountains of data, and fundamental economic and governance issues. Moving well beyond nature’s evolution roadmap, we have created incredible powers of information acquisition, we live longer lives, and we have greater capabilities than our forefathers would have ever believed possible. Additional convergences of biological and digital systems will take us to even higher levels of capabilities, but also increase complexities in society and create even more need for analysis capabilities.

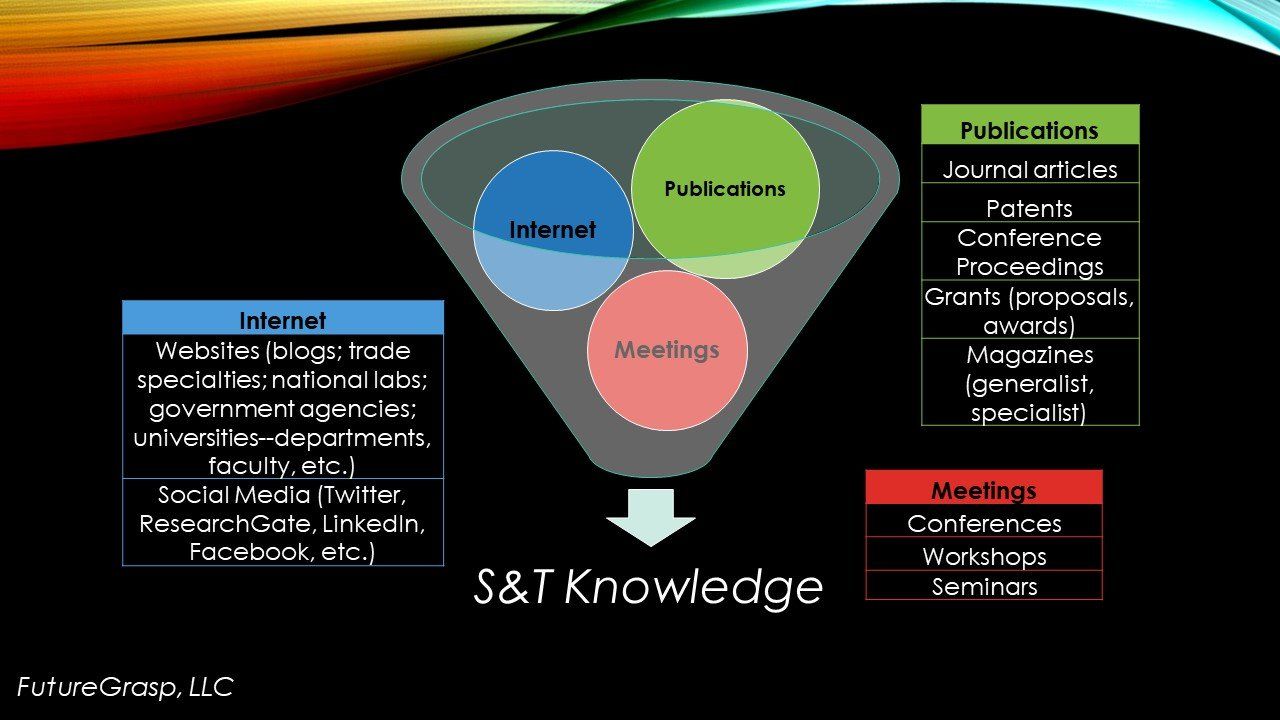

AI can assist us here. A vast and growing sector, AI – especially with deep learning - has the ability to process massive amounts of data, whether it be images, text, voice, numbers, etc. Numerous technology websites report on AI developments; for example, TechCrunch , CNET , Futurism , AINewsFeed. Visionary venture capital firms such as Bootstrap Labs focus on AI investments. [22]

There are daily reports of major advances by AI that go beyond what a human can accomplish. Art forgeries are detected with 99% accuracy from a single brush stroke. [23] Lip reading is done by an AI with greater accuracy than the best humans. [24] Skin cancer is detected by a deep learning trained AI algorithm with greater fidelity than dermatologists. [25] While still considered Narrow AI [26] , potential exists to expand these accomplishments into greater capabilities and thus to handle more complex problem sets. [27] Although progress to mimic a human in General AI [28] is slow presently, some researchers believe we have only begun to tap the full power of AI. [29]

The challenge before us is to develop AI quickly as our society increases in its economic, political, military and psychological challenges. We have a great future ahead of us, but only if we get help in unraveling the complexities of our modern world.

NOTES

[1] https://www.un.org/development/desa/publications/world-population-prospects-the-2017-revision.html , accessed 4 DEC 2017.

[2] Dominic Basulto, “Why Ray Kurzweil’s predictions are right 86% of the time,” Big Think 2012, http://bigthink.com/endless-innovation/why-ray-kurzweils-predictions-are-right-86-of-the-time , accessed 3 DEC 2017.

[3] https://www-01.ibm.com/common/ssi/cgi-bin/ssialias?htmlfid=WRL12345USEN , accessed 4 DEC 2017.

[4] For an overview of this issue, see “Evolving Ourselves – Redesigning the Future of Humanity—One Gene at a Time,” Juan Enriquez, Steve Gullans, https://www.amazon.com/Evolving-Ourselves-Redesigning-Future-Humanity-One/dp/0143108344/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1511886396&sr=8-1&keywords=evolving+ourselves+juan+enriquez , accessed 4 DEC 2017.

[5] Global Trends: Paradox of Progress, January 2017, https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/nic/GT-Full-Report.pdf , accessed 10/17/17.

[6] Global Trends, ibid.

[7] https://defensesystems.com/articles/2017/11/28/dod-dormant-data-ai.aspx , accessed 4 DEC 2017.

[8] https://blogs.nvidia.com/blog/2017/11/01/gtc-dc-project-maven-jack-shanahan/ , accessed 4 DEC 2017.

[9] http://www.news.com.au/technology/innovation/design/chinas-ai-pursuit-set-to-alter-future-economic-and-military-balance-of-power-report-claims/news-story/b6ad178bc555c30c8b817d582693ddff , accessed 4 DEC 2017.

[10] http://www.cnn.com/2017/11/29/politics/us-military-artificial-intelligence-russia-china/index.html , accessed 4 DEC 2017.

[11] https://www.theverge.com/2017/9/4/16251226/russia-ai-putin-rule-the-world , accessed 4 DEC 2017.

[12] http://www.india.com/news/world/new-zealand-develops-worlds-first-artificial-intelligence-politician-2678383/ , accessed 4 DEC 2017.

[13] https://www.wired.com/2017/05/hear-lets-elect-ai-president/ , accessed 4 DEC 2017.

[14] Or really any living being.

[15] Imagine a graph with two horizontal bars delineating the band within which one can function, outside of which one becomes diseased or dies. This homeostatic band is narrow for organic beings, and becomes even more narrow if we are immune compromised.

[17] http://www.pantagraph.com/business/investment/markets-and-stocks/jaw-dropping-facts-about-the-internet-of-things/article_f423bf71-1580-5d5d-a89d-6ebfd3201619.html , 25 NOV 2017, accessed 26 NOV 2017.

[18] In which they were declared co-winners of the first genome mapping by President Bill Clinton. The other national effort was by the National Institute of Health (NIH).

[19] “Inside the race to hack the human brain,” https://www.wired.com/story/inside-the-race-to-build-a-brain-machine-interface/ , accessed November 21, 2017.

[20] “AI-controlled brain implants for mood disorders tested in people,” Sara Reardon, 22 NOV 2017, http://www.nature.com/news/ai-controlled-brain-implants-for-mood-disorders-tested-in-people-1.23031 , accessed 4 DEC 2017.

[21] https://www.technologyreview.com/s/609232/the-surgeon-who-wants-to-connect-you-to-the-internet-with-a-brain-implant/ , accessed 4 DEC 2017.

[22] The author is honored to be a special advisor to Bootstrap Labs, https://bootstraplabs.com/ , accessed 4 DEC 2017.

[23] https://www.technologyreview.com/s/609524/this-ai-can-spot-art-forgeries-by-looking-at-one-brushstroke/ , accessed 4 DEC 2017.

[24] https://www.theverge.com/2016/11/24/13740798/google-deepmind-ai-lip-reading-tv , accessed 4 DEC 2017.

[25] https://newsroom.cisco.com/feature-content?type=webcontent&articleId=1887275 , accessed 4 DEC 2017.

[26] Narrow AI is defined loosely as an AI that attempts to execute a single task better than a human.

[27] https://www.futuregrasp.com/kardashev-scale-analogy , accessed 4 DEC 2017.

[28] General AI is characterized as an AI that has full cognitive capabilities that can mimic a human.

[29] http://www.aiindex.org/2017-report.pdf , accessed 4 DEC 2017.