AI National Plans: Their Necessity and Core Components

Artificial intelligence (AI) is one technology sector where strategic planning to guide diverse resources is especially valuable for governments. The consulting firm PwC estimates that AI will add $15.7 trillion to the world economy by 2030 [1] ; such eye-popping numbers don’t go unnoticed by senior policymakers of major governments. Consequently, several nation states are taking the initiative to get organized so that they may capitalize upon the algorithms that are driving the Fourth Industrial Revolution. [2] In addition to sponsoring large (in many nation states, multi-billion US dollar) R&D investments, a means toward this facilitation is to draft and execute AI national plans. Here we address the global need for such strategic documents, as well as the core aspects of them required for maximum effectiveness.

At this writing, only a few dozen nation states have published or have begun to draft AI national plans. A report soon to be published from the United Nations Interregional Crime & Justice Research Institute (UNICRI) and FutureGrasp, LLC [3] details that only 14 nation states have active AI national plans. Moreover, only 19 have expressed interest in developing one (as demonstrated by a working group formed and/or an outline or a white paper published toward an AI national plan). These are surprisingly low numbers, particularly considering the multi-decadal history of AI and the total of 193 sovereign states recognized by the United Nations.

Without a guiding document that encompasses the unique culture and capabilities of each nation state, there is the risk that AI will soon become beyond the direct control of some nation states. Given the deep infusion of AI into essentially every economic sector (including healthcare, finance, transportation and many others), inactive nation states will become reliant upon other countries, such as China, for their current and future computation. As every year goes by, the ability to catch up to those nation states that have active AI national plans will become increasingly difficult. Even the United States - which presently lacks an AI national plan, yet still leads AI overall because of its industry and academic domination - is not immune to being surpassed by other nation states that are more proactive in mustering their national capabilities. [4] [5]

It is the position of FutureGrasp, LLC that every nation state should have an AI national plan. To remain economically competitive, as well as to facilitate collaboration across borders, it is imperative that governments recognize the need to channel whatever resources they possess to organize strategic directions in the rapidly growing technology sector of AI.

Toward that end, here we detail a few core aspects of AI national plans that nation states should consider as they grapple with how to manage all the facets needed within the cross-cutting platform capabilities of AI. We also offer an example in each AI sector of a nation state that has considered it. From the earlier-mentioned UNICRI-FutureGrasp report [3], the AI sectors of core interest to any successful AI national plan are: Research, Infrastructure, Talent/Education, Industrial Strategy, Ethics/Legal Implications, AI in Government, and Data.

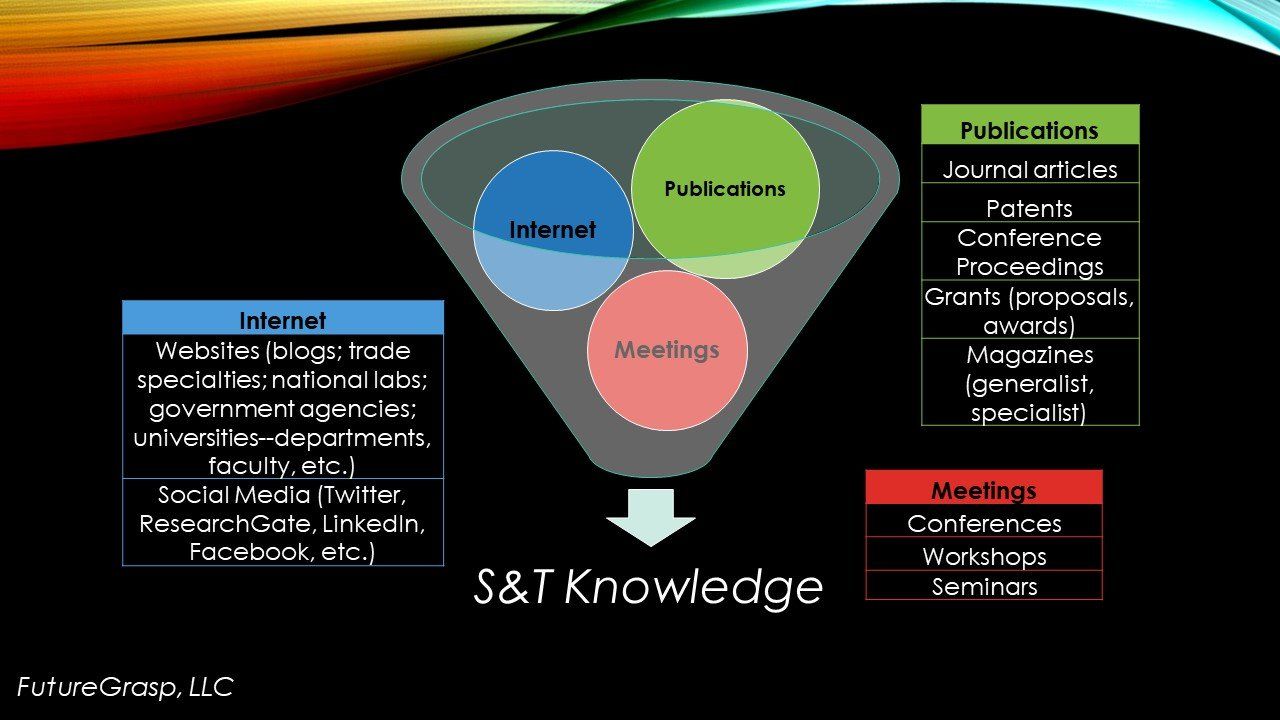

Research. Supporting a robust AI ecosystem is perhaps the most salient of all AI sectors. Like many emerging technologies, AI is in a dual-nature state of both current applications (for example, deep learning for facial recognition) and forward-leaning research (for example, advanced algorithms for autonomous vehicles). The only way to maintain an edge in AI is to fund basic research. While industry does sponsor significant research, such funding is driven ultimately by quarterly profits. Truly advanced research must be funded by governments. For example, DARPA [6] in the United States announced in September 2018 that they would fund US $2 billion to seek “contextual reasoning in AI systems to create more trusting, collaborative partnerships between humans and machines.” [7] While many nation states cannot afford US $2 billion in investments, even much smaller amounts can help advance the state of AI within a respective country. One strategic approach is to target a single niche area where a country has specific expertise and seek to become the world’s best at it; for example, AI analysis of video from autonomous vehicles. Funding new research centers, hubs and programs in basic and applied AI benefits nation states immediately with new employment, and long-term with new AI capabilities that can yield gains in government and the private sector.

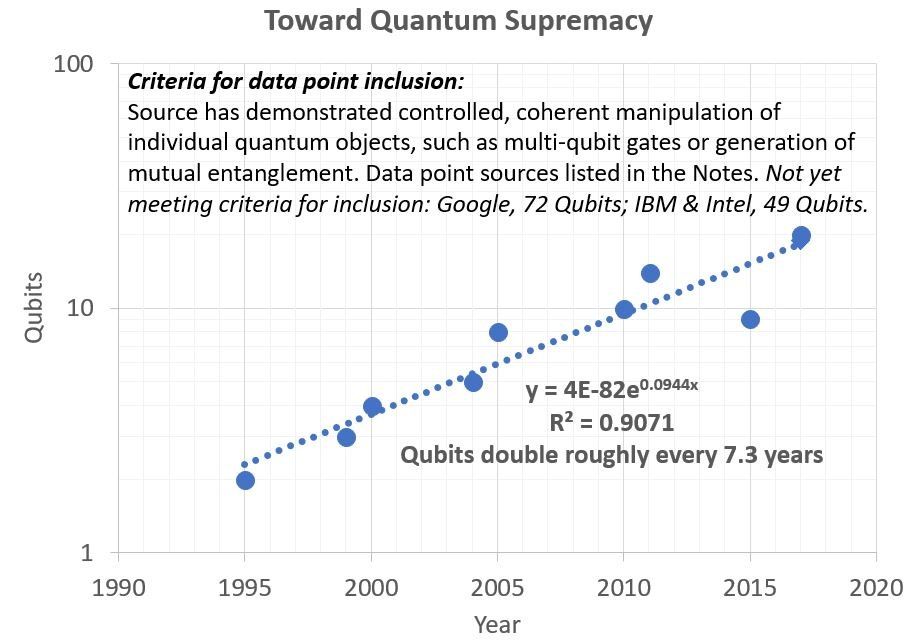

Infrastructure. AI is part of the digital ecosystem that surrounds us all. Beyond mere algorithms, AI requires the development of computational resources (semiconductors, enterprise systems, cloud computing), sensors (Internet of Things), and wireless services (3G, 4G and LTE now, 5G soon). AI infrastructure complements other needed national plans in those related technical spaces. Without this digital infrastructure, any AI national plan is doomed to be incomplete – having great algorithms is insufficient if one cannot provide data to them, compute them, and translate their results into meaningful output. A stellar example of a city-in-progress by Saudi Arabia that considers digital infrastructure to its fullest is that of NEOM, a US $500 billion initiative. [8] NEOM is designed to provide all the latest technologies (5G, Internet of Things, advanced compute), while simultaneously leveraging the full capabilities of applied AI.

Talent/Education. People are what makes technology tick. Necessary for a successful AI national plan are core aspects of the talent/education AI sector: a robust education system (particularly in STEM – science, technology, engineering and mathematics); welcoming immigration policies for people with top AI talents; funding for university scholarships and faculty chair positions; promoting diversity among AI researchers; and lifelong learning and retraining programs. An example of commitment from a nation state in their AI national plan toward talent/education is the United Kingdom. Within their plan, they devote several paragraphs to “Work with schools, universities and industry to ensure a highly skilled workforce; Enable access to high-skilled global talent; and Take steps to promote diversity in the development of AI.” [9] Commensurate funding of hundreds of million British pounds (£) is assigned to support this critical AI sector.

Industrial Strategy. The transition of government-funded R&D into the private sector is a critical component of any AI national plan. This handoff can be catalyzed by funding to AI startups and promotion of innovation ecosystems (for example, industrial parks). An example of successful industrial strategy execution is Canada. Within its Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy, [10] Canada highlights industry engagement as a core component of its AI national plan. Moreover, Canada backed up their words with funding: “Canada did a lot in 2017 to build on our AI research advantage with more than CAN $300-million [US $229 million] in new funding for research and $260-million [US $199 million] raised by Canadian AI startups.” [11]

Ethics/Legal Implications. AI has potential to create disruption in the legal community, especially in the context of ethics implications. For example, if an autonomous vehicle causes an accident, who is legally responsible: the programmer? the car manufacturer? the passenger? Ethics also enter prominently into such discussions. If an autonomous vehicle has to make a split-second decision whether to swerve and crash into a telephone pole (thus potentially killing the driver) or to steer toward and potentially kill a pedestrian, which is the correct ethical choice? The permutations of such debates rapidly increase with more people involved and more complex systems. Rather than leaving ethics after incidents to the philosophers and legal issues to the lawyers, it behooves governments to infuse such issues into their AI national plans. Regulations for the application of AI can then be established that benefit society as a whole. The South Korean AI national plan [12] is an exemplar of tackling this issue. Within that plan is mandated the task to “Establish a charter of ethics for Intelligent IT to minimize any potential abuse or misuse of advanced technology by presenting a clear ethical guide for developers and users alike (2018).”[12]

AI in Government. Governments are often the most complex organizations and biggest employers within a nation state. It makes sense then to leverage applied AI within government to increase efficiencies, enhance communications to the public, and manage government agencies in general. Italy may be unique among nation states with the initial focus in its AI national plan upon how its government might leverage AI in its public administration. The Italian Government, led by a task force [13] , released a white paper on AI in March 2018, Artificial Intelligence: At the Service of Citizens. “The objective is to facilitate the adoption of these technologies in the Italian Public Administration, to improve services to citizens and businesses, thus giving a decisive impulse to innovation, the proper functioning of the economy and, more generally, to progress in daily life.” [14]

Data. Machine learning and deep learning algorithms require data, and lots of it. Fortunately, governments have incredible volumes of data: tax records, health information, economic trends, census data, and many more 1s and 0s fill government computers. The challenge is to harness that information in a meaningful manner so AI algorithms can apply it, while still adhering to privacy constraints and other data policies. With its recent AI national plan, France presents a good example of how to develop data policies for applied AI. Of the six parts of its plan, Part I is titled “An Economic Policy Based on Data.” Within that section is detailed how France will leverage its strengths in data management while keeping in mind European policies, such as the GDPR. [15] To avoid “spreading efforts too thinly,” the French Government proposes to focus upon only four sectors initially: healthcare, environment, transport mobility and defense-security.

As the field of AI continues to accelerate, nation states

that become engaged now will have an advantage long-term compared to inactive nation

states. The AI sectors detailed above offer nation states key points to

consider as they strategize and enter initially or engage more deeply in the exciting

world of AI.

Notes (all weblinks accessed March 2019)

[1] “Sizing the prize - PwC’s Global Artificial Intelligence Study: Exploiting the AI Revolution,” 2017, https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/data-and-analytics/publications/artificial-intelligence-study.html

[2] Klaus Schwab, “The Fourth Industrial Revolution: what it means, how to respond,” January 14, 2016, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/01/the-fourth-industrial-revolution-what-it-means-and-how-to-respond/

[3] United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI) & FutureGrasp, LLC; “Artificial Intelligence: State Initiatives & Crime and Justice Implications,” in final edits and reviews.

[4] Kai-Fu Lee, “AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order,” 2018, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

[5] Joshua New, December 4, 2018, “Why the United States Needs a National Artificial Intelligence Strategy and What It Should Look Like,” Center for Data Innovation, http://www2.datainnovation.org/2018-national-ai-strategy.pdf

[6] Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency

[7] “DARPA Announces $2 Billion Campaign to Develop Next Wave of AI Technologies,” September 7, 2018, https://www.darpa.mil/news-events/2018-09-07

[8] T. Zareva, October 30, 2017, “Saudi Arabia Is Building a $500-Billion New Territory Based on Tech and Liberal Values,” https://bigthink.com/design-for-good/saudi-arabia-is-building-a-utopian-city-to-herald-the-future-of-human-civillization

[9] “Industrial Strategy; Artificial Intelligence Sector Deal,” https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/702810/180425_BEIS_AI_Sector_Deal__4_.pdf

[10] “CIFAR Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy,” https://www.cifar.ca/ai/pan-canadian-artificial-intelligence-strategy

[11] S. Irvine, “From startups to champions: How to focus Canada’s AI dreams,” February 2, 2018, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/rob-commentary/from-startups-to-champions-how-to-focus-canadas-ai-dreams/article37836853/

[12] “Mid- to Long-Term Master Plan in Preparation for the Intelligent Information Society Managing the Fourth Industrial Revolution,” Government of the Republic of Korea—Interdepartmental Exercise, https://english.msit.go.kr/cms/english/pl/policies2/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2017/07/20/Master%20Plan%20for%20the%20intelligent%20information%20society.pdf

[13] “IA Task Force,” https://ia.italia.it/task-force/

[14] “Artificial Intelligence—At the Service of Citizens,” March 2018, Task Force on Artificial Intelligence of the Agency for Digital Italy, https://ia.italia.it/assets/whitepaper.pdf

[15] General Data Protection Regulation