Digital Twins and Digital Doubles: Populating our Virtual Worlds

Digital Twins

Years ago when I worked in the semiconductor crystal growth industry, we had a frequent problem with crystal defects that occurred, seemingly at random, during a multi-day growth process. These defects caused total failure of the greater than $80,000 single crystal. One of my proposed solutions was to create a dynamic computer model of the whole system. The simulation would run simultaneously with the real system’s control settings and model in real-time the various potentials for defects well in advance of their occurring. The closed-loop SCADA [1] system would then make appropriate corrections to avoid defects and yield a perfect crystal. While theoretically possible, my proposal was unfortunately ahead of its time in terms of the compute power and sensors required vs. those available in the early 2000’s.

Fast forward to today, and this concept is called a ‘digital twin,’ defined as “a virtual model that is essentially the intelligence counterpart to an actual, physical object.” [2] Now digital twins are becoming relatively common - “Gartner predicts that by 2021, half of large industrial companies will use digital twins, resulting in those organizations gaining a 10% improvement in effectiveness.” [3]

Digital twins rely on three main components: data (from sensors in the Internet of Things, IoT); a ‘digital thread’ that relays information to the digital twin [4] ; and computation (from artificial intelligence, AI). Fortunately, all three are now up to snuff enough to enable useful applications of digital twins. For example, in the oil and gas industry, predictive maintenance via digital twins offers tremendous benefits:

“The digital twin is a system of systems based on a virtual digital copy of all the infrastructure assets as represented by Deep Learning Neural Networks (DNNs). DNNs are a Machine Learning technique that brings us a new paradigm of ‘software that writes software’ and acts as a compiler for your data to deliver the desired outcome…There is no doubt that smarter, faster, AI-powered applications and digital twins can have a fundamental effect on predictive maintenance in the oil & gas industry, but it will also pave the way for AI and GPU infrastructure enabled edge-to-cloud capabilities to enable full-stream outcomes for production optimization, automated drilling and even bridging the silos across all the operational streams from oil exploration and extraction to processing and distribution.” [5]

While industrial systems may be relatively straightforward to simulate, could we advance this concept dramatically to simulate a living human, thereby creating a ‘digital double’? What benefits and applications might be created if we have a virtual simulacrum of ourselves with all our knowledge, health status, personality quirks, and worldviews? With faster compute, increasing volumes of data, the creation of multi-purpose platform apps, and artificial intelligence (AI), we are getting close to realizing digital doubles. The implications could be profound.

Platform Apps

In the fiction book, “The Circle,” by Dave Eggers [6] , a single company becomes the mashup equivalent of Google, Facebook, Amazon and sundry other companies in its effort to “close the circle” and obtain total digital control and transparency among all global citizens. The book resonated with many people in the technology community, as it is not a far cry from what we see already in China and Silicon Valley.

A close real equivalent to the fictional company Circle is the Chinese firm WeChat (developed by Tencent), which is simultaneously a messaging, social media and mobile payment digital platform. As of March 2018, WeChat has over 1 billion users. Moreover, it is close to being a dominant platform for mobile users – “Chinese users spend approximately one third of all their time on mobile in WeChat.” [7] WeChat is in the vanguard of multi-app consolidation and control.

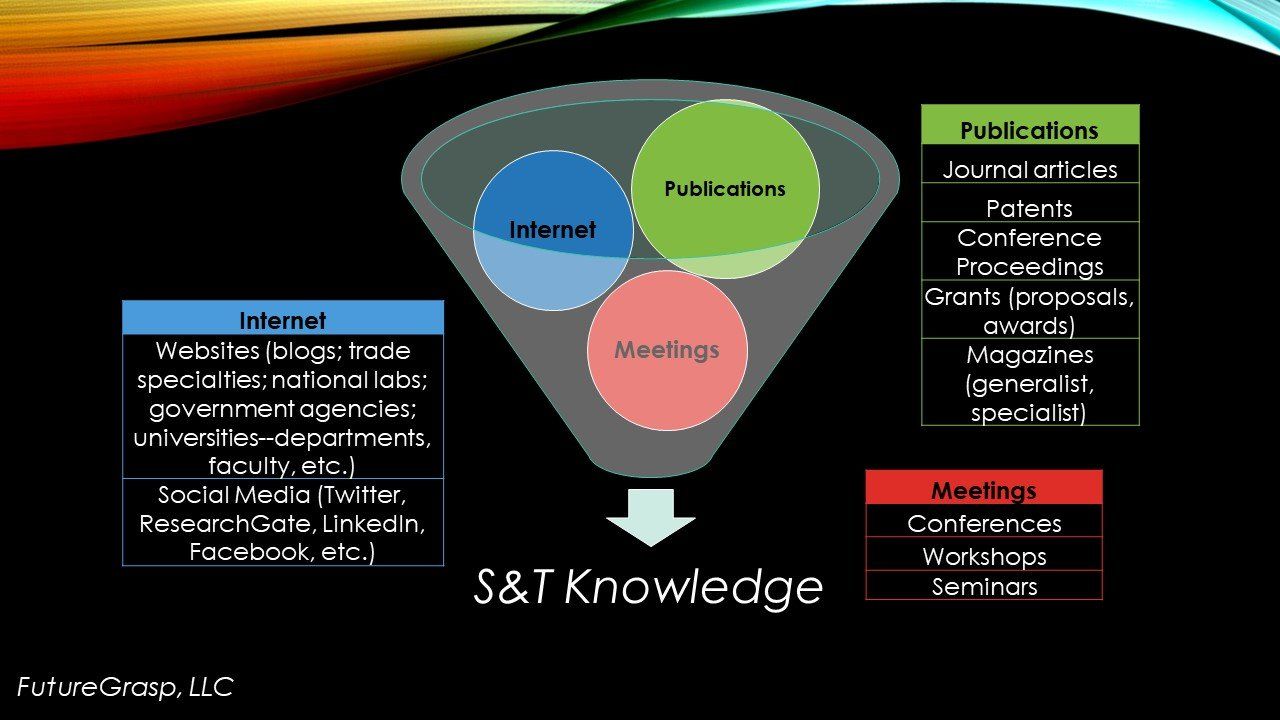

As with WeChat, the past decade has seen the emergence of platform apps with many capabilities all packaged under a single user-login. Facebook, Amazon, Alibaba and Google are paradigms of what software companies can become through strong programming and rapid absorption of their competition. Apple (iPhone), Samsung (Galaxy), and Google (Android) show what hardware firms can accomplish by stuffing ever more AI processing power into a smartphone. By becoming go-to platform apps, these companies have positioned themselves as five of the top ten – Apple, Amazon, Alphabet, Microsoft and Facebook - in market capitalization listings. [8]

Thus, the trend is clear toward continuing consolidation of capabilities under a handful of umbrella app platforms. The full manifestation of this app-merging would be for each of us to get a digital double – “virtual models of ourselves that will interact with each other in countless simulations to help us make faster, more informed choices in our daily lives.” [9] Such virtual humans would offer significant benefits.

Digital Doubles

In a recent article in Scientific American , Pedro Domingos expounds upon what he sees as a trend in the AI community toward the digital double. Prof. Domingos researches what he dubs the “Master Algorithm,” [10] a fusion of deep learning, symbolic learning, evolutionary algorithms, analogical methods and Bayesian learning. Promises for the Master Algorithm’s benefits are significant:

“Once we attain the Master Algorithm and feed it the vast quantities of data each of us produce, artificial intelligence systems will potentially be able to learn very accurate and detailed models of individual people: our tastes and habits, strengths and weaknesses, memories and aspirations, beliefs and personalities, the people and things we care about, and how we will respond in any given situation. That models of us could essentially predict the choices we will make is both exciting and disquieting.” [9]

An important step for digital doubles is to create seamless voice communications. Several forward-thinking digital companies have marketed voice-activated systems. Apple voices Siri; Microsoft offers Cortana; and Amazon gives us Alexa. While still far from perfect, with more data and continuous improvements in compute, the time will come soon where it will be normal to have a conversation with a computer.

But voice is only one component of a digital double—even more critical is the modeling of an actual person. A few companies are leaders in this space. IPsoft offers the digitized human of Amelia, which possesses cognitive learning abilities, autonomic task management, and emotional intelligence. Amelia services a range of industries like banking, insurance and healthcare to remove much of the drudgery of customer assistance. [11] The company Oben “is building a decentralized AI platform for Personal AI (PAI), intelligent 3D avatars that look, sound, and behave like the individual user.” One can then use that avatar to perform tasks that one may not have time for or would rather not execute. [12]

What might be some applications for a digital double? Let’s review some possibilities.

· Communications – Digital doubles would have the capacity to chat with each other. Suppose you’re planning a party and want to invite all your best friends. You tell your digital double to contact all their digital doubles and arrange the date, time, who brings what, etc. All the knowledge of your friends' calendars, likes/dislikes, and anything else that might affect the outcome of the event could be considered in the virtual world and then brought into reality at the big event.

· Travel – Your virtual persona could be the ideal travel agent. It would know what you prefer to do, where you want to visit, your comforts and discomforts, and really anything else that might affect your personal travel. Moreover, it could navigate all those multiple apps for booking your airline flight, hotel room, rental car, tickets, etc. It could even help you take and choose which photos to post later in social media.

· Knowledge Acquisition – Instead of typing into Google to find that random factoid you want to know, if you have a digital double you could just ask them. With full internet access, your digital double would be able to find any piece of information you’d want within milliseconds. Knowing your interests in great detail, your digital double could also suggest additional information beyond the original search.

· Healthcare – A Holy Grail for a digital double would be to have it mimic essentially the entire human body, in all its nuances. This might be the last stage of the development of virtual self-avatars, as the complexity of the body (37.2 trillion cells in the human body [13] , 100 billion neurons in the human brain [14] ) would challenge even the most advanced supercomputers of today. Nevertheless, we could make basic simulations of the body in digital doubles and thus aid doctors in diagnosing diseases, optimizing nutrition, and assisting in exercise.

Conclusions

Industry already leverages digital twins to streamline equipment maintenance, identify potential part failure modes, and automate more of its processes. The capabilities of digital twins will only improve with better sensors, faster cloud and edge computing, and ever-improving AI.

Will society take the next step and simulate actual humans in the form of digital doubles? I believe it is inevitable. Many of us already have a substantial digital presence, whether in Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, WeChat or other social media sites. We spend increasing amounts of time online. A next step for our digital lives would be to create digital doubles that know the most intimate details of us. Benefits for those with a constantly learning virtual self-avatar could be substantial.

As we move into the future with more advanced compute and exponential data availability, there will be an inexorable push to simulate more of our world. Populating our digital worlds with digital twins and digital doubles will ultimately serve us greatly in our increasingly complex real worlds.

Notes (all links accessed September 2018)

[1] Supervisory control and data acquisition

[2] “Using AI, IoT and Big Data to Deliver Digital Twins,” September 2, 2017, https://insidebigdata.com/2017/09/02/using-ai-iot-big-data-deliver-digital-twins/

[3] C. Pettey, “Prepare for the Impact of Digital Twins,” September 18, 2017, https://www.gartner.com/smarterwithgartner/prepare-for-the-impact-of-digital-twins/

[4] “Industry 4.0 and the digital twin,” Deloitte Consulting, 2017, https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/cn/Documents/cip/deloitte-cn-cip-industry-4-0-digital-twin-technology-en-171215.pdf

[5] P. Modi, “How AI Is Providing Digital Twins For Predictive Maintenance In Oil And Gas,” June 21, 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/nvidia/2018/06/21/how-ai-is-providing-digital-twins-for-predictive-maintenance-in-oil-and-gas/

[6] D. Eggers, “The Circle,” 2013, Alfred A. Knopf & McSweeney’s Books, San Francisco, https://www.amazon.com/dp/B00EGMQIJ0/ref=dp-kindle-redirect?_encoding=UTF8&btkr=1

[7] M. Brennan, “One Billion Users And Counting -- What's Behind WeChat's Success?,” March 8, 2018, Forbes, https://www.forbes.com/sites/outofasia/2018/03/08/one-billion-users-and-counting-whats-behind-wechats-success/#57ecfb57771f

[8] “The Largest Companies By Market Cap (100),” http://www.symbolsurfing.com/largest-companies-by-market-capitalization

[9] P. Domingos, “Our Digital Doubles,” Scientific American, pp. 88-93, September 2018.

[10] P. Domingos, “The Master Algorithm: How the Quest for the Ultimate Learning Machine Will Remake Our World,” 2015, Basic Books, New York, NY, https://www.amazon.com/dp/B012271YB2/ref=dp-kindle-redirect?_encoding=UTF8&btkr=1

[11] IPsoft, https://www.ipsoft.com/amelia/

[12] Oben, https://oben.me/

[13] E. Bianconi, et al., “An estimation of the number of cells in the human body,” July 5, 2013, Annals of Human Biology, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3109/03014460.2013.807878

[14] “The Human Memory,” http://www.human-memory.net/brain_neurons.html