Why Stop at Voice?

Sitting in a coffee shop this morning, I heard a man at the table next to me take a call on his smartphone. He proceeded to speak so loudly that all the patrons had no difficulty hearing all the nuances of his small business. It was quite distracting, so I departed the comfortable environment earlier than I’d planned. Incidents like this make me wonder about the future of voice as the dominant control method for computers in the future. Voice is all the buzz (no pun intended) in Silicon Valley. Many technology leaders (Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, etc.) are betting that verbal commands will soon be the major means of communication for our numerous devices. But is verbal chatter the terminal point for our computer communications? Are we destined solely for the Star Trek Enterprise’s command prompts, to be stating the contemporary equivalent, even in public forums, of “Computer, take me to the Bridge”?

TODAY’S VOICE TECH

We naturally try to emulate our biological capabilities in the computer. Why wouldn’t we want to just talk to our devices and have them both accurately record our words, as well as chat with us like a human would? As a result of intense interest in deploying voice commands, tremendous advances have been made since the early days of voice recognition. Algorithms powered by artificial intelligence (AI) now can achieve up to 95 percent accuracy in understanding voices, on par with humans. [1] Depending how fast one can type vs. speak, voice commands offer the potential to be more efficient, and perhaps more accurate, than the output from our standard QWERTY keyboards. [2]

Top tech firms are embracing voice—Amazon has Alexa, Apple has Siri, and Microsoft has Cortana. We can talk to small receiving stations like Amazon’s Echo and Google’s Home and order just about anything…all by using our natural voice. Companies such as IPsoft have even captured a real human’s likeness and digitized it into an efficient enterprise software system to answer repeatedly, and to millions of customers simultaneously, mundane questions about insurance and human resource related matters. [3] Despite these advances and promises, there exist challenges with voice that may compromise its full deployment.

CHALLENGES WITH VOICE

Even we humans frequently misinterpret what each other is saying, so it’s no surprise that algorithms also make mistakes. Several particular linguistic challenges come to mind that could be onerous for a machine to overcome completely:

Noisy environments. The “Cocktail Party problem” is encountered frequently at conference receptions. All of us have a unique voice, even if it can change a little based upon our mood, fatigue or alcohol consumption. Nevertheless, throw in a bunch of other voices and background noise, and we can be challenged in interpreting the voice that we wish to focus upon, even if the speaker is right next to us. And that’s with a lifetime of learning; for an algorithm with little such experience, such a situation can be even more difficult. To cut through the cacophony of extraneous noise, one approach by Google is to incorporate both audio and visual cues using a machine learning algorithm trained upon thousands of YouTube videos. [4] Further advances may be needed to ensure no misinterpretation of a speaker in noisy environments.

Confusing command prompts. A recent story highlights the dangers of being completely trusting of a verbal command system. A family with an Amazon Echo system accidentally had an entire private dialogue of theirs emailed to a colleague several miles away – without the family’s knowledge. Per Amazon:

“Echo woke up due to a word in background conversation sounding like ‘Alexa’. Then, the subsequent conversation was heard as a ‘send message’ request. At which point, Alexa said out loud ‘To whom?’ At which point, the background conversation was interpreted as a name in the customer’s contact list. Alexa then asked out loud, ‘ contact name , right?’ Alexa then interpreted background conversation as ‘right’.” [5]

Better safeguards – for example, double-prompts, or additional codes and keywords – may be needed for such systems to ensure conversations meant to remain private are kept private.

Accents. Accents are one of the joys of language, but they also can be a burden for interpretation by an algorithm. Impressively, Amazon Alexa, Google Home, and Apple Siri test surprisingly well against speakers with multiple accents saying identical phrases, but there are still occasional failures. [6] Interpreting different accents may be compounded by other factors such as background noise.

Slang and dialects. Two beautiful aspects of language are slang words and dialects that can be almost entirely distinct from a mother tongue. For example, in German language ‘Umgangssprache’ (slang) can be an intense experience for even the fluent speaker. Throw in the differences among ‘Hochdeutsch’ (high German), ‘Plattdeutsch’ (low German), ‘Schweizerdeutsch’ (Swiss German), and other dialects even from village to nearby village, and one can become confused quickly. Prior to my post-doctoral studies in Germany, my wife and I spent four months intensively studying Hochdeutsch and felt ourselves reasonably fluent enough to go into stores and order items with no issues. Then we moved to a village 10 kilometers outside the city where we learned German and went to a local grocery store. It seemed they had a different word or pronunciation for almost every item that we had ordered easily back in the big city. The issue was a dialect, almost distinct from Hochdeutsch, that we had not been taught. Voice algorithms working in such environments would have to learn all such nuances to be proficient.

Language changing. Another great thing about languages is that they are never static. New words are constantly being introduced, especially in areas of technology. Words also change their root meaning, progressing through so-called ‘soft changes’: “Words tend to pick up different usages and even meanings over time, often very remarkably. The word terrific used to have a highly negative meaning—something that terrifies. Only recently has it become a positive term.” [7] Just as humans must adapt to the morphing of a language, algorithms will also have to constantly maintain updated dictionaries and be on the lookout for words that are used in different ways than commonly heard.

Foreign languages. There are almost 7,000 globally recognized languages, although one might consider that among this Tower of Babel, we really only use about 10 or 20 languages prominently around the world. [8] , [9] Roughly two billion people speak only three languages (Chinese--including 10 varieties, Spanish and English). [10] Nevertheless, to truly become the main, go-to, approach for computer commands, must our algorithms become the equivalent of the Star Wars C3PO, whose fictional robotic abilities could accommodate over six million galactic tongues? Would introducing more languages also compound interpretation among them all? For example, could a word that was pronounced by a Chinese Mandarin speaker be misinterpreted, and thus mistranslated, as Korean? When Amazon Alexa was debuted in France, Amazon had to consider the occasional English American word creeping into French conversation. More data is critical to understand the nuances of Romance languages with multiple versions of “you” and other honorifics. [11]

BEYOND VOICE

Aside from writing or typing, we have many non-verbal ways of communicating – facial expressions, eye motions, musculoskeletal movements, even our thoughts themselves can be harnessed by a computer to convey what we mean. Brain-computer interfaces (BCI) have been researched for decades in attempts to tease out our thoughts. Similar to audio commands, however, challenges with all of them exist. The ability of a computer algorithm to interpret our thoughts is a research avenue that has attracted substantial interest, especially in the last few years. With the goal of discussing technologies that could be more widely accepted in the near term, we describe below exclusively examples of ex-vivo (out of the body) capabilities. [12]

Facial expressions can be used to detect basic wishes. A Brazilian team is working to use facial expressions to control a wheelchair for individuals lacking other means of controlling mobility. “The camera can identify more than 70 facial points around the mouth, nose and eyes. By moving these points, it is possible to get simple commands, such as forward, backward, left or right and, most importantly, stop.” [13]

Tracking pupil oscillations (pupillometry) is another approach for non-verbal commands. Researchers in France and The Netherlands showed in 2016 a new BCI method via pupillometry. “In our method, participants covertly attend to one of several letters with oscillating brightness. Pupil size reflects the brightness of the selected letter, which allows us–with high accuracy and in real time–to determine which letter the participant intends to select. The performance of our method is comparable to the best covert-attention brain-computer interfaces to date, and has several advantages: no movement other than pupil-size change is required; no physical contact is required (i.e. no electrodes); it is easy to use; and it is reliable. Potential applications include: communication with totally locked-in patients, training of sustained attention, and ultra-secure password input.” [14]

Measurement of thoughts directly is also generating strong interest in the research community. In 2016, Elon Musk announced the creation of the company Neuralink , which seeks to create an external system to read the electrical signals from one’s mind and thus control computers and merge with artificial intelligence (AI). [15] “Neuralink is developing ultra-high bandwidth brain-machine interfaces to connect humans and computers.” The venture raised over $27 million in late 2017. [16] A wonderful posting in Wait But Why goes into detail on the underlying technology. [17]

In April 2018, a graduate student at MIT created a system that uses electrical signals from muscles to capture thoughts without speaking. Called AlterEgo, the system was tested on 10 subjects and achieved 92 percent accuracy. “AlterEgo is a closed-loop, non-invasive, wearable system that allows humans to converse in high-bandwidth natural language with machines, artificial intelligence assistants, services, and ‘movements—simply by vocalizing internally.” Potential applications include air traffic control and military communications. [18]

IMPLICATIONS & CONCLUSIONS

Living in the mountains of Colorado, I rarely hear much traffic, planes or other noises that are common in more populous urban areas. But every time I travel to a big city, I am struck by the almost constant cacophony of sounds. Noise pollution is a recognized health issue. [19] While talking to a computer may not be a major contributor to noise, every decibel can be a distraction, whether it be in a coffee shop, in a cube farm at work, or at home with your spouse and kids. Non-verbal communication approaches have the potential to create a quieter world.

Individuals who have lost the ability to speak or communicate otherwise certainly could leverage non-audio BCI systems. Paraplegics, autistics and other handicapped people (for example, those with a speech impediment) could benefit tremendously from a system that is well-trained to their thoughts. Being trapped in one’s mind with no means of communication must be torture for such disease or accident victims. BCIs have great potential to help them engage more with the world.

Perhaps in the future we may extend the use of BCIs into the science fiction realm of telepathy, also. Imagine being able to communicate non-verbally with your relatives or friends, not only while in the vicinity of each other, but perhaps many miles apart. We already do this now with texting, but using our thumbs still requires physical contact with a smartphone (and can be very dangerous when driving). Using a BCI such as those described above could enable more seamless communications in many life situations.

Ultimately, instead of having to answer a cell phone call verbally in a coffee shop, might we soon instead be able to communicate effectively without saying a word? The technologies to get us there are in labs and test computer algorithms now. It remains to be seen how soon such capabilities will be widely available. Sometime soon, we might instead think , “Computer, order me a triple latte.”

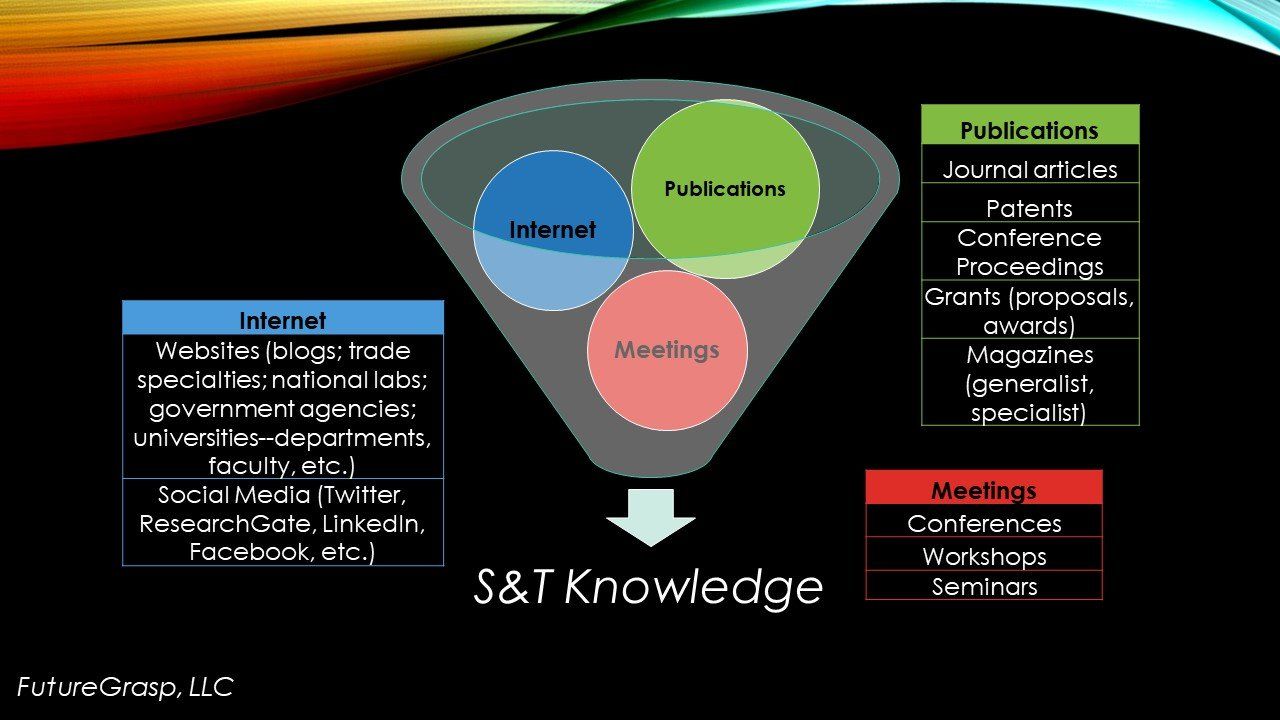

NOTES (all websites accessed June 19, 2018)

[1] K. Wiggers, “Qualcomm claims its on-device voice recognition is 95% accurate,” May 25, 2018, https://venturebeat.com/2018/05/25/qualcomm-claims-its-on-device-voice-recognition-is-95-accurate/

[2] QWERTY keyboards were initially designed to actually slow us down in typing so that the manual typewriter keys would not jam. It’s funny how legacy technologies remain in modern use even if they are sub-optimal.

[3] S. Kesler, “Inside the bizarre human job of being a face for artificial intelligence,” June 5, 2017, https://qz.com/996906/inside-the-bizarre-human-job-of-being-a-face-for-artificial-intelligence/

[4] L. Tung, “Google AI can pick out a single speaker in a crowd: Expect to see it in tons of products,” April 13, 2018, https://www.zdnet.com/article/google-ai-can-pick-out-a-single-speaker-in-a-crowd-expect-to-see-it-in-tons-of-products/

[5] S. Wolfson, “Amazon's Alexa recorded private conversation and sent it to random contact,” May 24, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/may/24/amazon-alexa-recorded-conversation

[6] M. Calore, “Watch People With Accents Confuse the Hell Out of AI Assistants,” May 16, 2017, https://www.wired.com/2017/05/ai-assistants-accented-english/

[7] A. Myers-Stanford, “How artificial intelligence can teach itself slang,” June 7, 2017, https://www.futurity.org/deep-learning-language-1452822-2/

[8] S.R. Anderson, “How many languages are there in the world?,” 2010, Linguistic Society of America, https://www.linguisticsociety.org/content/how-many-languages-are-there-world

[9] “List of languages by number of native speakers,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_languages_by_number_of_native_speakers

[10] J. Myers, “These are the world’s most spoken languages,” February 22, 2018, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/02/chart-of-the-day-these-are-the-world-s-most-spoken-languages

[11] B. Barrett, “Inside Amazon's Painstaking Pursuit to Teach Alexa French,” June 13, 2018, https://www.wired.com/story/how-amazon-taught-alexa-to-speak-french/

[12]

These examples are not intended to be an exhaustive review of the BCI field,

but merely demonstrative of the art of the possible.

[13] A. Pasolini, “Wheelchair controlled by facial expressions to hit the market within 2 years,” May 19, 2016, https://newatlas.com/wheelchair-facial-commands/43206/

[14] Sebastiaan Mathôt, Jean-Baptiste Melmi, Lotje van der Linden, and Stefan Van der Stigchel, “The Mind-Writing Pupil: A Human-Computer Interface Based on Decoding of Covert Attention through Pupillometry,” PLoS One. 2016; 11(2): e0148805. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4743834/

[15] T. Lacoma, “Everything you need to know about Neuralink: Elon Musk’s brainy new venture,” November 7, 2017, https://www.digitaltrends.com/cool-tech/neuralink-elon-musk/

[16] Neuralink, Crunchbase, https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/neuralink

[17] T. Urban, “Neuralink and the Brain’s Magical Future,” April 20, 2017, https://waitbutwhy.com/2017/04/neuralink.html

[18] AlterEgo, MIT Media Lab, https://www.media.mit.edu/projects/alterego/overview/

[19] N. Lee, D. Anderson, J. Orwig, “Noise pollution is a bigger threat to your health than you may think, and Americans aren't taking it seriously,” January 26, 2018, http://www.businessinsider.com/noise-pollution-effects-human-hearing-health-quality-of-life-2018-1